what is co-design?

This page builds on McKercher, K. A. (2020). Beyond sticky notes. Doing co-design for Real: Mindsets, Methods, and Movements, 1st Edn. The page is updated regularly and continues to be a work in progress. If you’d like to use the diagrams please contact us for permission and a high-resolution version. 📖

As you read, bring your insight, identity and experience with you. You know things about co-design.

-

There are many histories and practices of paid and unpaid designing.

We acknowledge and pay our respect to First Nations peoples and practitioners - who have been designing for thousands of years without toolkits or sticky notes.

We acknowledge design that comes from and within communities’ efforts for survival, joy, mutual aid, imagining new worlds and other things. As Lesley-Ann Noel et al remind us: ”Every community practices the design of itself, independent of expert knowledge.”

We build on the work of many friends and colleagues — especially Ingrid Burkett, Liz Sanders, Penny Hagen, Simon Harger-Forde, Kataraina Davis, Emma Blomkamp, Liz Wren, Vikki Reynolds and the Design Justice↪ movement. 🪜

-

This page is authored by KA McKercher (them/they) author of Beyond Sticky Notes. KA’s approach comes from 14 years of ongoing and daily practice of co-design and their support and supervision of other practitioners internationally.

KA is a white, queer and neurodivergent person living in Australia with lived experience as a victim-survivor. They’re originally from Aotearoa.

KA is a university-educated designer, facilitator and professional supervisor.

KA has led co-design processes for 13 years across Australia and Aotearoa across mental health, LGBTQIA+ health, disability, domestic violence, community health, public health, medical research and more.

KA takes an explicit justice-focused, trauma-informed and pluriversal approach [1] to their work, rejecting and challenging many of the extractive and exclusive practices of commercial design and mainstream project work.

KA is always learning.

[1] See Design Justice and Reynolds, V. (2012). An ethical stance for justice-doing in community work and therapy. ↪

[2] For example: See Noel, L. A., Ruiz, A., van Amstel, F. M., Udoewa, V., Verma, N., Botchway, N. K., ... & Agrawal, S. (2023). Pluriversal Futures for Design Education. ↪

-

here are the words we use in early 2024

co-design

Co-design brings together lived experience, lived expertise and professional experience to learn from each other and make things better - by design.

Co-design involves centering care, working with the people closest to the solutions, sharing power, prioritising relationships, being honest, being welcoming, using creative tools, balancing idealism and realism, building and sharing skills.

Co-design uses inclusive facilitation that embraces many ways of knowing, being and doing.

co-design crew or team

A design crew or team is small group of people who learn and make things together. Generally, a co-design crew or team is made up of people with lived experience, lived expertise, professionals and provocateurs.

co-designer

Someone who is part of a co-design team through most or all of a co-design process (from planning through to delivery).

provocateurs

Provocateurs are part of the co-design team and outsiders to the context. They deliberately don’t have professional expertise in the field and might not have lived experience either. They bring their curiosity and can soften the power differences between politicians, professionals, peers and community members. We learned this practice from Simon Harger-Forde at Innovate Change.

lived experience

Personal knowledge about the world gained through direct, first-hand involvement in everyday events rather than through representations constructed by other people. Source: Oxford Reference↪. Shared by Morgan Cataldo↪

lived expertise

What has been learned through lived experience and how it’s applied. Source: Lived Experience Leadership – Understanding and Defining the Roles. ↪Shared by Morgan Cataldo↪

power

Someone’s ability to do something – for example, set an agenda or decide what engagement happens. Source: Our work on All of Us - NSW Health↪

safety

Safety can be physical, emotional, legal and cultural. No one should be harmed by their experience of engagement. Learn what we meant by safety. Source: Our work on All of Us - NSW Health↪

co-design is designing with, not for

Co-design brings together lived experience, lived expertise and professional experience to learn from each other and make things better - by design.

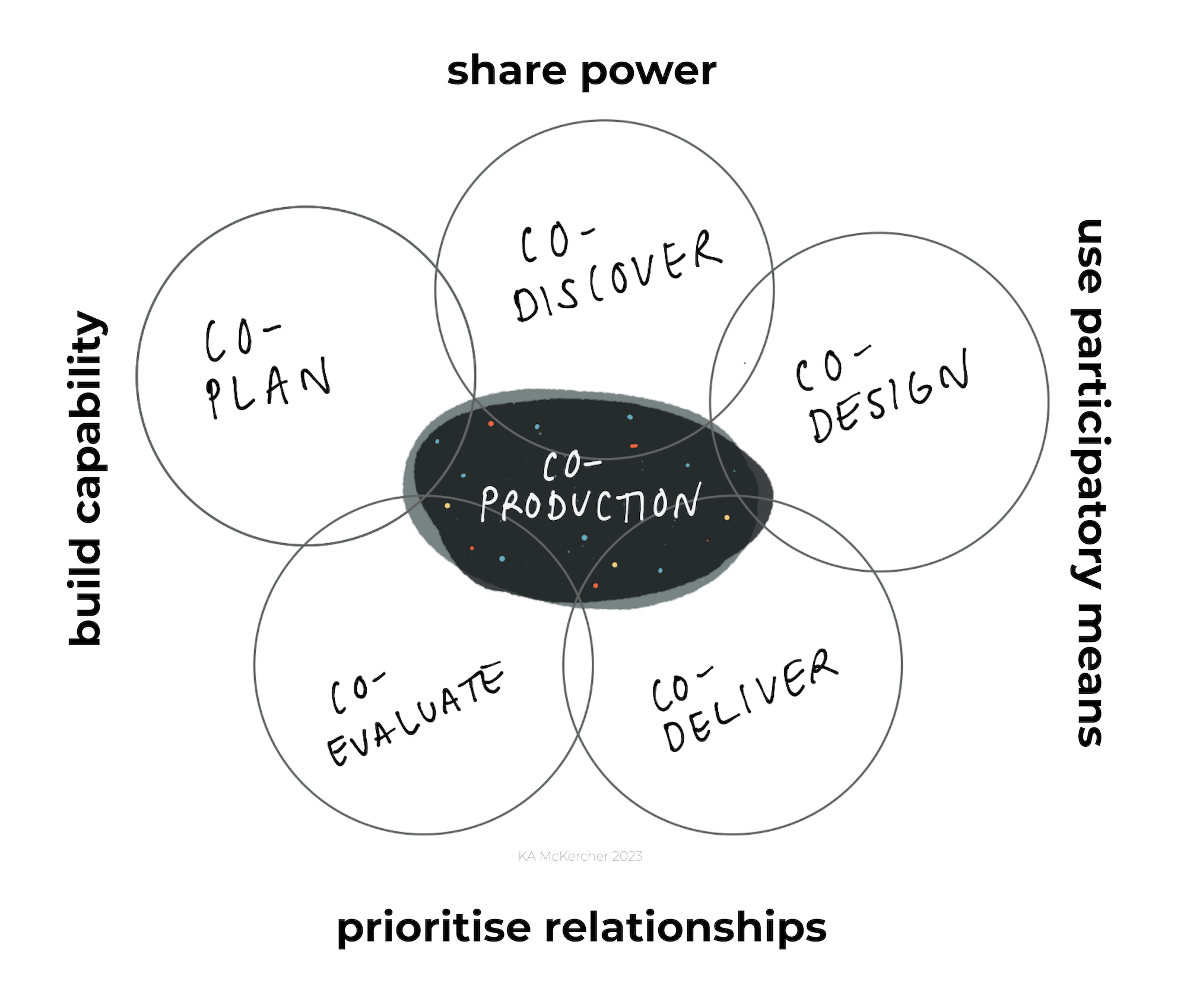

Co-design is part of co-production.

Co-design (Figure 1) involves centering care, working with the people closest to the solutions, sharing power, prioritising relationships, being honest↪, being welcoming, using creative tools, balancing idealism and realism, building and sharing skills. Co-design uses inclusive facilitation that embraces many ways of knowing, being and doing.

Co-design has a ‘co’ bit (e.g. community, co-operation) and a ‘design’ bit. Both parts (community and design) are important, but neither has all the answers.

We break co-design into three parts:

Co-design as a movement

Co-design as processes, mindsets↪ and principles

Co-design as an ever-expanding set of creative and care-full methods and tools

As a movement, co-design challenges the power of people who make important decisions about others’ lives, livelihoods and bodies. Often with little to no involvement of the people whom the decisions will impact.

Figure 1 Image description: Five circles sit around a central circle reading 'co-production' - they read co-plan, co-discover, co-design, co-deliver and co-evaluate. Around the edges are four principles: share power, use participatory means, prioritise relationships, and build capability.

co-design principles

there are many ways to work together

here are four principles that support effective co-design

-

When differences in power are unacknowledged and unaddressed, the people with the most power have the most influence over decisions. Co-design is about sharing power in planning, research (sometimes called discovery), designing and deciding what gets implemented.

-

Co-design isn’t possible without relationships and trust. Sometimes communities don’t trust organisations or external consultants. Often for good reasons. Building that trust takes time. It can’t be rushed. You can’t buy trust; it can only be earned – the better the social connection, the better the co-design process and outputs.

-

Co-design is about people taking part. That means offering many ways for people to take part and express themselves, for example, through visual, kinaesthetic and oral approaches. Co-design doesn’t rely only on writing, slideshows and reports. Participatory approaches facilitate self-discovery and move people from meeting participants to active partners.

-

With enough time and care, co-design can build new knowledge and skills for everyone involved.

Some people need support and encouragement to take on different ways of being and doing, learn from others, and have their voices heard. To support that, facilitators and designers can move from ‘expert’ to coach, enabler or host. Everyone has something to teach and something to learn.

co-design processes

there is no one-size-fits-all co-design process

Instead, there are principles and processes to apply differently with different people and places. There are culturally-specific practices, too [1]. Figure 2 and the Model of Care for Co-design↪ describe our approach, beginning with building or strengthening the conditions for ethical, necessary and safe (enough) involvement of people who usually haven’t worked together before. We built our approach from generative design and social innovation processes [2] as co-design involves design.

co-designers make decisions, not just suggestions (Burkett, 2012)

Figure 2 Image description: Co-design process. A hand-drawn circular diagram reads: build the conditions, immerse and align, discover, design, test and refine and implement and learn. The circle is unending.

[1] For example - see Sheehan, Tamwoy et al, St John & Akama, Akama, Whaanga-Schollum & Hagen, Auckland Co-design Lab

[2] For example - see the UK Design Council, NESTA, Sanders and Stappers, This is Service Design Doing

-

Co-design can reproduce systems and practices of oppression without a commitment to justice-doing [1]. Co-design isn’t inherently good or right for every project.

So, we’re learning to resist and challenge:

Claiming that there’s one way to co-design. There isn’t.

Over-focusing on problem-finding and problem-solving. Co-design can also focus on strength, joy, opportunity, resistance, survival, community and more.

Gathering more stories of harm when harm has been well-documented and strategically ignored.

Reinforcing certain bodies and minds’ value over others (i.e. neuronormativity [2] cisnormativity, ableism)

for example through only providing one way to do an activity or engage (such as forcing cameras on in virtual meetings)Rushing to workshops and making decisions before building shared understanding, access and relationships.

Using outdated meeting formats and facilitation techniques.

Forcing vulnerability, connection or fun.

Sanitising language that hides or conceals reality. Language must be brave, care-full, honest and descriptive.

Seeing constraints as inherently bad. Constraints can also be creative and useful.

Believing co-design is inherently inclusive and failing to make necessary adjustments when it fails to include people.

Focusing only on new ideas and overlooking what’s already strong.

Rushing to evaluate co-designed things before they’ve had sufficient time to show reliable signals of impact.

[2] We continue to learn about neuronormativity from Sonny Jane Wise (The Lived Experience Educator). ↪

some questions you might ask at each stage

You don’t have to answer all the questions. You’ll have your own, too.

The questions can help you think practically, responsibly, critically, generatively or reflectively. You might use the questions with the Model of Care for Co-design↪ and alongside other tools.

-

what’s our understanding of co-design?

is co-design needed? who gets a say?

is co-design possible with our relationships, timeframe, budget, project sponsor and other factors?

what scope of practice do I/we bring to co-design? read about scope of practice

what’s my/our role in the process?

e.g. should we lead, host, quietly support in the background or something else? what do we need to consider?in whose interests is co-design being proposed?

where is the work already happening?

whose goals and values are/will shape the co-design process?

who will be able to take part? who won’t?

what care-full language might we use?

what mindsets and values are we coming to co-design with?

what knowledge, experience, skills and influence might we need among co-designers and others involved in the process?

what do people need to know to decide if they want to/can be involved in co-design?

what assumptions are we making about how, when and where co-design might happen?

-

what can and can’t be co-designed?

what’s already working? what advocacy is underway?

what’s already known?

in whose worldview has knowledge been created?

where might the process start?

is more research needed? will more research create harm?

what strengths and access needs do co-designers have? how are we meeting needs for predictability?

what are we noticing about the people and group/groups we’ve formed to co-design?

what is a warm and informative welcome for co-designers?

-

We use the term ‘(re)discover’ to acknowledge that much is already known and may have been restricted, repressed, or strategically ignored. Some knowledge may need to be synthesised and shared differently.

Coming into co-design, co-designers (especially with lived experience) will often have unequal access to information compared to ‘professional’ co-designers.

how can current knowledge be made more accessible?

what’s happening in the/our context?

What’s already strong?how will we build shared understanding without enforcing sameness?

What insights can we name?

How might we share the insights accessibly?

-

are we ready to start designing? e.g. we have insights and design principles that we’ve written down, talked about and/or made visual

who’s doing the making?

do we need something new?

what can we build on?

what making skills can you access - with and beyond co-designers? e.g. using paper, using technology, using natural materials or something else

whose values will guide the decision-making process for idea selection and progression?

are we holding our ideas lightly?

how are we scanning for unintended consequences? i.e. undermining something good in the system already

-

are we open to learning?

what are we trying to learn? with who?

what aren’t we testing?

what’s our understanding of the difference between a prototype and pilot?

are we testing the thing being co-designed (e.g. a product) as well as if there are sufficient enabling conditions for the thing to succeed? e.g. the organisation or system

what’s worth taking forward? according to whom?

-

how might we pause and celebrate the work we’ve done? or, make space for grief if we weren’t successful

how can we make co-presenting more accessible to people with lived experience? e.g. through pre-recording

how can we continue the ‘co’ beyond co-design? e.g. into co-delivery, co-delivery, co-governance or something else

how are we staying true to the direction set by co-designers?

what can we share with co-designers? e.g. impact, new learning, new roles and opportunities or something else

about the co-designed thing

are we prototyping, piloting or something else?

what signals are we noticing? e.g. about reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, sustainment [1]

where are we on the long arc of change?

how will we know an ending, pause or phase shift is needed?

about the co-design process

what was the experience of co-designers?

did we raise or lower the standard of co-design? How?

what did we show to be possible?

what did/will we leave behind for future historians and auditors?

co-design mindsets

Using co-design tools, processes and methods must be paired with a commitment to the mindsets of co-design. Mindsets are ways of being and thinking that support co-design.

We describe six core mindsets↪ that we find helpful to support everyone involved in co-design. We practice these mindsets alongside trauma-informed practice (e.g. offering choice, building predictability, supporting self and collective care).

Image description: Six mindsets for co-design branch-off around a brain drawing. Coming off the brain are six mindsets: elevating the contributions and leadership of lived and living experience, valuing many perspectives, learning through doing, practising curiosity, being in the grey and offering generous hospitality.

differences from other approaches

There are lots of ways to work together.

The diagram below describes different levels of community involvement in designing (for example, products, places, services, communications, systems or something else). It also describes who typically has the power to make decisions.

We build from Arnstein’s ladder (1969), from Sanders and Stappers, the design justice movement and make the levels of participation specific to designing.

Access a text-based version of this diagram here.

Co-design and human-centred design (HCD) are different. While fuelled by good intentions, design for people often ends up as designer-centred, staff-centred or organisation-centred by implementation when community are rarely involved in decision-making.

Usually, design by communities is already happening. We can find it if we care enough to look. We can choose to act in solidarity not in competition.

”Every community practices the design of itself, independent of expert knowledge.”

Noel et al (2023) Pluriversal Futures for Design Education

co-design and lived experience/expertise

There are different sources of lived experience (see: Safe + Equal)

lived experience doesn’t belong to one sector or experience

having lived experience doesn’t automatically mean that we can run co-design in a useful, responsible and inclusive way - facilitating and coordinating co-design are skills

having people with lived experience involved or in a meeting/workshop doesn’t automatically make something co-design

lived experience-led doesn’t mean a project, process or service is inherently just, usable or free from harm

while stories matter, elevating lived experience is more than collecting and sharing stories - many stories have already been collected and ignored.

how to tell if it’s co-design

You might ask these questions (and others) to determine if something is co-design. Remember, just because something isn’t co-design doesn’t automatically make it less useful, inclusive or worthwhile.

Co-design isn’t the only way or always the best way.

-

Design is about making things - for example, products, services, policies, campaigns, communications, buildings and places or other things.

Only having meetings, sharing information or making plans usually doesn’t involve enough design to be called co-design.

-

In co-design everyone contributes to the design in some way. That might be through creating design principles, creating concepts, making prototypes and models, creating content or something else.

Professional design skills (such as digital design and architecture) are still important and useful to making things that work.

-

Co-design is about working together or working towards working together.

If different groups are working independently or in separate committees the work likely isn’t co-design.

Sometimes people with lived experience and professionals aren’t ready to work together. Don’t force togetherness.

-

Co-designers must be recognised for their time and not coerced into volunteering.

Recognition means different things to different people. Talk about what recognition means to different people. Offer choices and get creative about what can be offered.

-

Co-design isn’t about extracting information. Co-design must also have benefits for the people involved (and possibly for their families and broader communities).

Benefits could be learning new skills, getting paid, making new connections or something else.

co-design as a social movement

To make co-design happen we need systems, organisations and communities to embrace the leadership and contributions of people with lived experience. Doing that requires different ways of thinking and being, which are missing from many teams, organisations and systems.

The table below describes several social movements that are necessary to make co-design a reality and a norm.

| From | To |

|---|---|

| Making decisions for people with lived experience | Making decisions with people with lived experience |

| Valuing professional expertise above all | Valuing professional and lived experience equally |

| Seeing marginalised people as a burden | Seeing marginalised people as resilient, creative and capable |

| Colonising, heteronormative and ableist systems | Compassionate systems that see and respond to dimensions of difference |

| Believing that resources are scarce to make change | Seeing an abundance of experience, ideas and energy for change |

| Focusing on ‘consumer’ councils and committees | Embedding participation in everyday practice |

| Rushing to solutions | Slowing down to listen, connect and learn |

| McKercher, K. A. (2020). Beyond Sticky Notes. Doing Co-design for real: mindsets, methods and movements. | |

conditions for co-design

Even with good intentions, community buy-in and quality facilitation, co-design can be derailed. Here are some conditions that can support co-design.

| 1 Support and sponsorship | 2 Time and money |

|---|---|

| We need people to endorse and reinforce the approach we're taking and the outcomes we want to achieve. Sponsors and supporters help to build commitment, remove obstacles and overcome resistance as and when it arises. | To do co-design we need time and money for: Facilitation and convening (co-design is not free) Paying people with lived experience for their time and for any expenses Investing in approaches (after they have been co-designed) Supporting lived experience capability and leadership Prototyping, testing and learning (prior to implementation) Communicating the work throughout to build commitment |

| 3 Culture and climate | 4 Commitments |

| Supportive culture and climate includes: Authorising environments from formal and informal leaders A focus on learning not control Connective tissue to share learning, failure, success Support to adopt the mindsets, especially when we regress to old ways of being Support to develop the skillsets for co-design Accountability to the people we engage through co-design (they can call us out) |

Commitment to co-design looks like: Focusing on outcomes (value) over outputs (busyness) Following through into implementation Staying committed to elevating the voice and contribution of lived experience Practising cultural intelligence and widening inclusion Partnering, not parenting Sharing decision making, power and attribution Value and reciprocity with co-designers |

| Kelly Ann McKercher, 2020 |

what co-design is not

-

Everyone has a role in co-design. Communities know things professionals don’t, and professionals know things communities don’t. Where possible, co-design brings professional and lived experience together. Learning together produces stronger solutions that consider different needs and perspectives.

-

Co-design should not ignore evidence of what works or existing advocacy, projects or strengths. Instead, conveners work hard to:

- bring relevant evidence into the process in accessible ways

- critique of existing evidence and methods of evidence-generation

- notice what people in a context are already trying to change and how

- bring more value to everyday people’s stories and experiences -

Co-design can cost more than a consultation in the short term. However, with co-design, we pay now to avoid paying later. Co-design builds long-term commitment. By contrast, consultation often gives the illusion we’ve bought people on board - only to have them fall overboard when implementation starts. With consultation, we pay later - often in costly, public and damaging ways.

-

Being a minority in any group can be intimidating, hostile and unsafe. Professionals lacking curiosity and self-awareness often force people with lived experience to defend their experience and identity. Co-design strives for equal (if not greater) numbers of community members and professionals.

-

Co-design is more than having workshops. It’s also about connecting with people one-to-one, trying things out, learning new skills, pre-briefing and debriefing and including co-designers in decision-making. Not everyone can or wants to contribute to a workshop.

-

Being dishonest breaks trust. Don’t tell people you’re co-designing if you’re not. Be honest about what decisions have already been made and what limits there are to what you’re doing. Trust that people will decide if they want to work with you without the need to exaggerate the change they might make.

-

Not everyone has the privilege to volunteer their time.

Don’t expect or coerce community members to give their time for free.

Talk about what recognition means to them. Be up-front about what you can offer, financial and non-financial.

If you’re not doing co-design, don’t say that you are.

want to know more about co-design? contact us, buy the book or explore paid or free tools

Information

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

Shipping

Returns Policy

The lands we work on are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land. We Pay the Rent and support First Nations Futures. We acknowledge Ancestors and Elders past and present and the many traditions of design, creativity, collective care and innovation that have always been here.